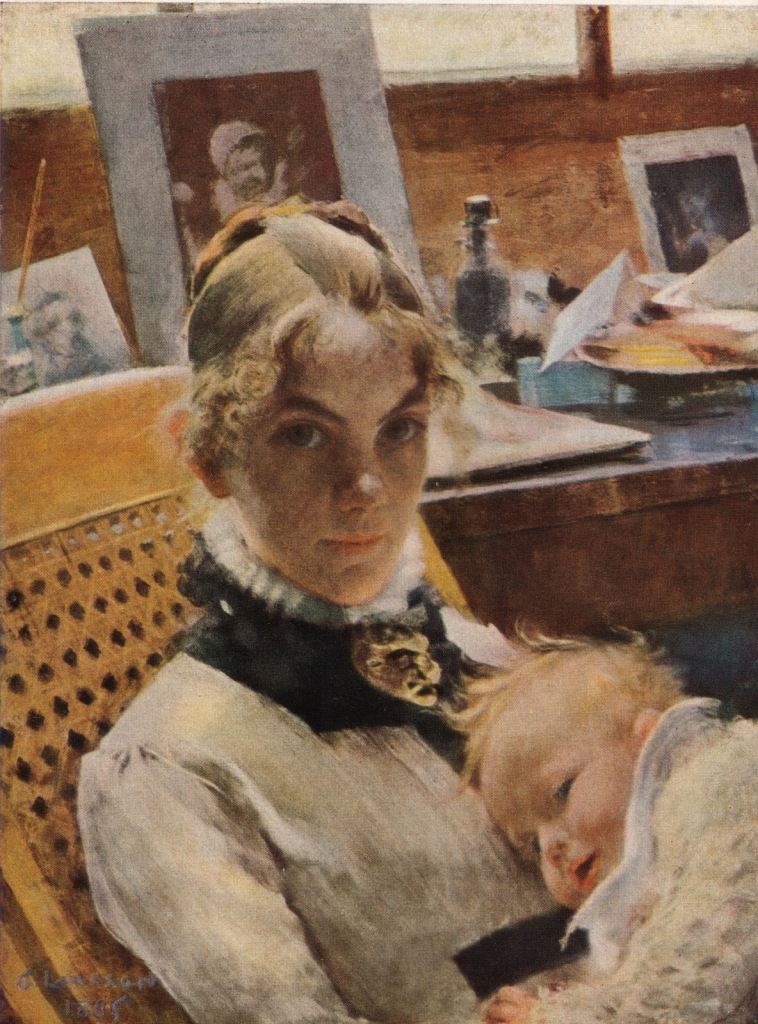

Carl and Karin Larsson married in late 1882 and in 1884 their first child, Suzanne was born. Their second child, a son Ulf, was born in 1887 but sadly died when he was eighteen. In all, Carl and Karin had eight children. After Ulf came Pontus in 1888, Lisbeth in 1891, Brita in 1893, Mats in 1894 but he died aged just two months, Kersti in 1896 and finally Esbjörn in 1900. It is quite obvious that Karin’s time was taken with the upbringing of their children.

In 1888 the couple returned to Sweden with their two children and on deciding to settle permanently in Sweden Karin’s father, Adolf Bergöö, gave them a wooden cottage in the countryside of central Sweden, which had belonged to relatives. The house named Lilla Hyttnäs, was situated in the town of Sundborn, in Falun Municipality, 250 kilometres north-west of Stockholm.

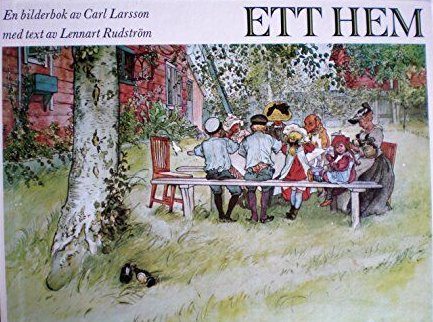

Carl remembered his first visit to the cottage accompanied by his father-in-law and in his 1899 book, Ett Hem (A Home) he wrote:

“…The cottage stood right on a bend in the Sundborn River, just where it gets a smidgeon wider. Everything inside was spick and span, the furniture was simple, but old fashioned and robust, handed down by their parents, who had lived in the vicinity. While I was here, I experienced an indescribably delightful feeling of seclusion from the hustle and bustle of the world, which I have only experienced once before (and that was in a village in the French countryside). When my Father in law suggested buying me a small property in the same village, I declined, saying that only something resembling this little idyll would suit an artist…”

Lilla Hyttnäs soon became Carl and Karin’s mutual art project in which their artistic talents found expression in a very modern and personal choice of colour schemes and interior design. The couple favoured bright colours, and filled the rooms with handcrafts, which mirrored the Arts and Crafts Movement which had inspired them. The Arts and Crafts movement was an international trend in the decorative and fine arts that first emerged in the mid-nineteenth century in the British Isles and then spread to the rest of Europe and America.

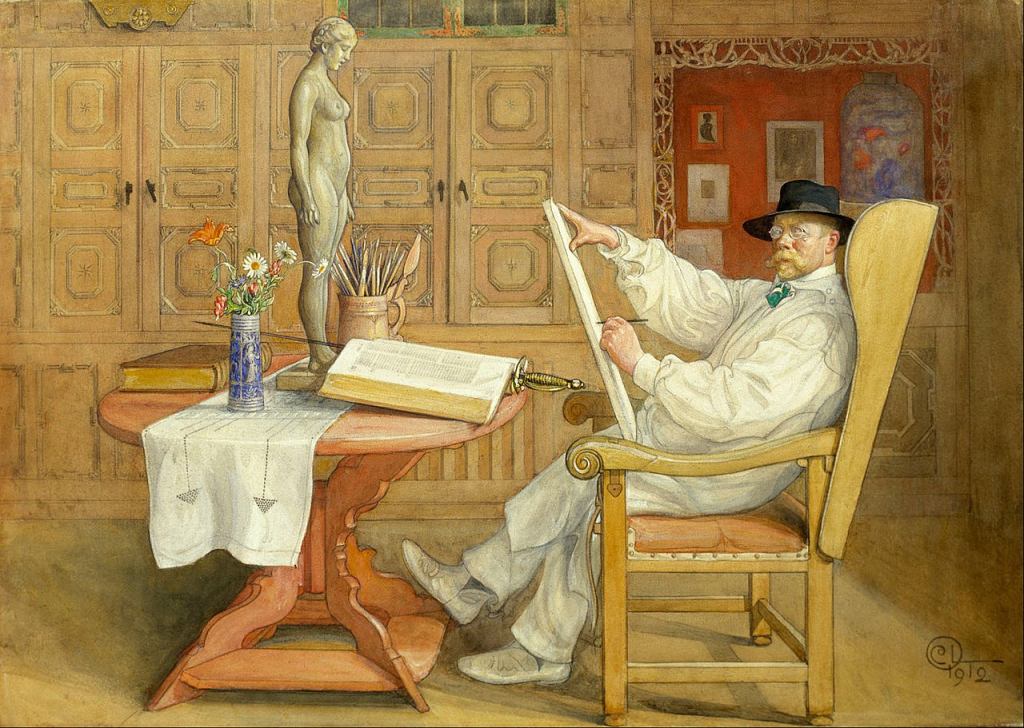

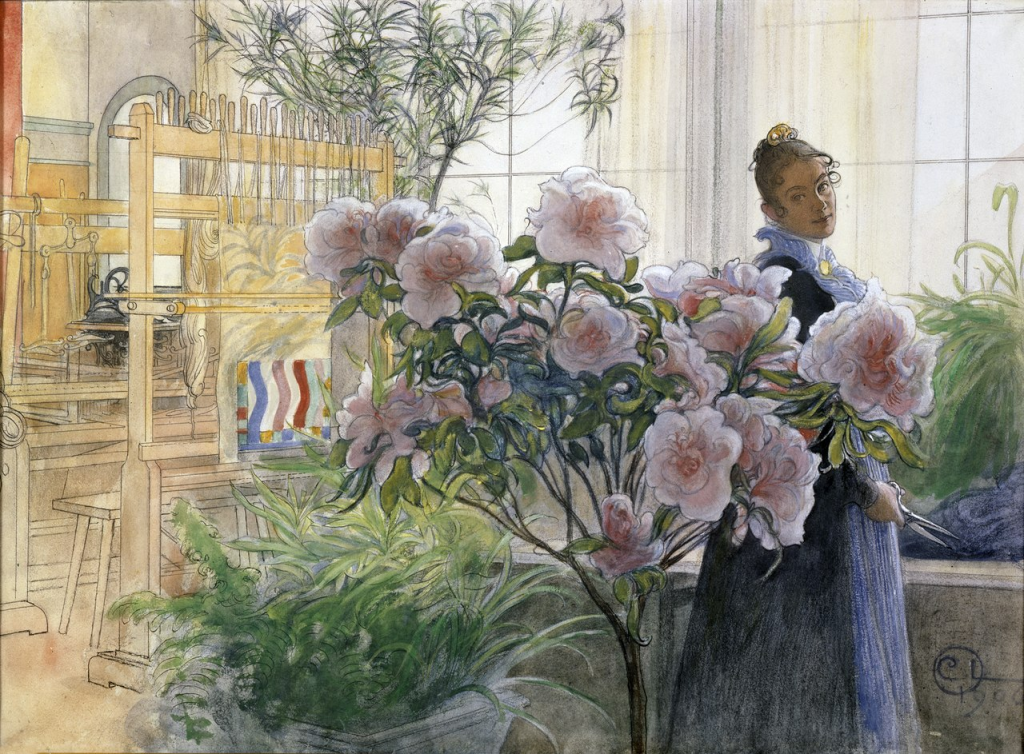

Karin Larsson was a young mother, but on top of that she was an ambitious woman who although she had stepped back from her painting, she had replaced the canvas with other artistic goals that would see her use needles, thread and silks instead of brushes and paint. She would now concentrate on home furnishings which would brighten up the old cottage. The cottage interior had now taken the place of the canvas. Her great inspiration was William Morris, who was a leader of the English Arts and Crafts movement, and she liked to incorporate foliage designs across her upholstery. Karin’s husband, Carl, created a series of twenty-six watercolours, entitled A Home which depicted the beautiful interior designs of his wife.

Karin Larsson spent mch time designing fabrics for their furniture. One example of this is the chair cover (below).

Her beautifully, highly colourful designs were used for bench cushion covers.

The transition from painting to textile art and home furnishings by married females was in those days an acceptable evolution and was not seen as something forced upon them by their husbands. In the work she lovingly put together to create their home she was able to express herself through the medium of textiles, and furniture design.

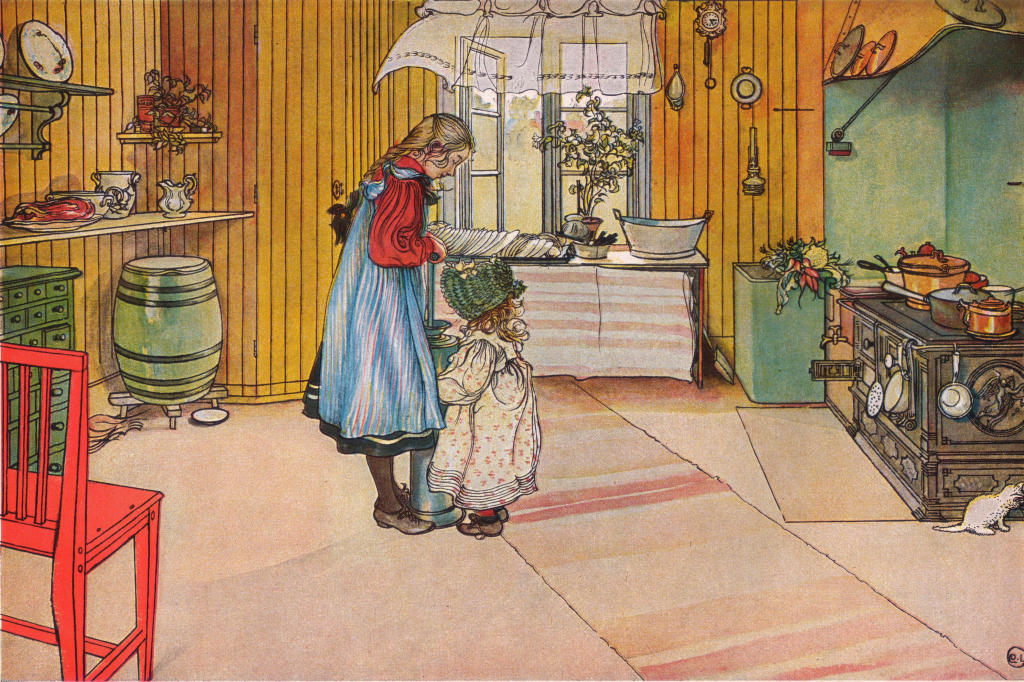

Karin’s life at Lilla Hyttnäs was tiring. She had to cope with the everyday house chores and eight children to manage. Her eighth child, a son, Esbjorn had been born in 1900. However, she still found time to design and weave a large amount of the textiles which she utilised in her home. She also spent time embroidering, and designing clothes for herself and the children. The aprons, known as karinförkläde in Swedish, were worn by her and the other women who worked at the house.

Carl Larsson’s bedroom at Lilla Hyttnäs was a through-room. The door is wide open to the end room where his wife and the smaller children slept. The white four-poster bed with embroidered curtains stands in the middle of the floor. It has several ingenious features, such as a bench, a chamber-pot cupboard and a small, built-in bedside table. Look closely at the background and you will see that this is also a self portrait as we can just observe the artist, looking in a mirror, doing up his collar buttons.

The interiors of the Larsson home were characterised by rural simplicity. Nevertheless, every detail was carefully designed, with influences from England, Scotland and Japan.

The kitchen, which was first and foremost a place for household chores, did not display the same modern interior style and comfort as the rest of the house.

Through Larsson’s paintings and books their house has become one of the most famous artist’s homes in the world. The descendants of Carl and Karin Larsson now own this house and keep it open for tourists each summer from May until October. The rooms of the house featured in many of Carl’s paintings and books.

Besides depictions of their home featuring in his artwork which highlighted Karin as a talented interior designer, Carl featured his wife and children in many of his paintings.

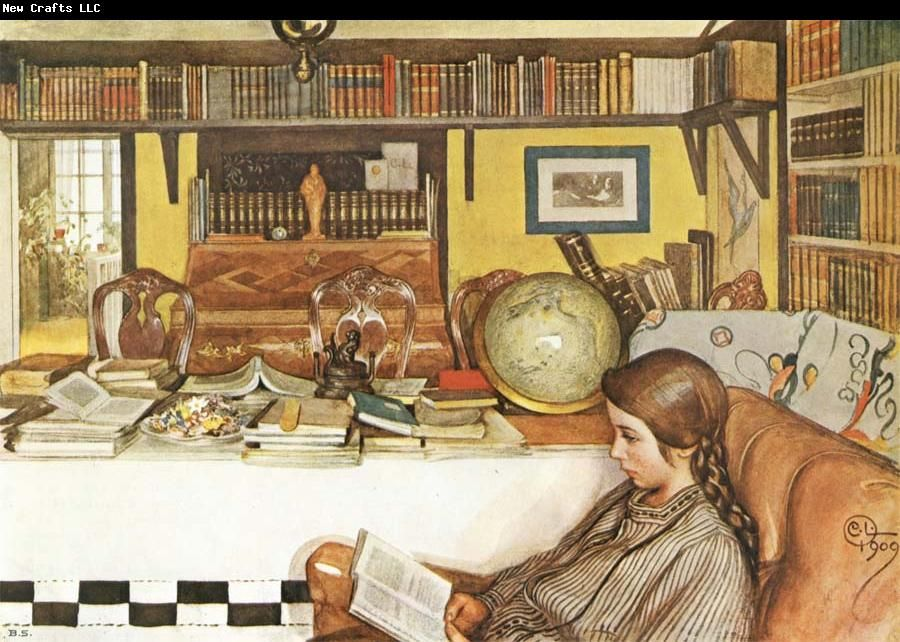

In 1905 Carl featured his seventh child, eleven-year-old Kersti in his watercolour work.

In his 1890 watercolour it was his third-born child, two-year-old son, Pontus, who featured.

The Christmas spirit was captured in some of his family portraits.

Carl and Karin’s fifth child, daughter Brita, was depicted as Idun or Iduna, the Norse goddess of Spring and rejuvenation. Norse mythology tells us that Idun was the keeper of the magic apples of immortality, which the gods must eat to preserve their youth. Iduna carried her apples in a box made of ash (called an eski), along with her fruit, and this box served as one of Idun’s major symbols.

Carl Larsson travelled away on a number of occasions leaving the household and his children the sole responsibility of his wife. Karin employed the carpenters and painters needed to transform Lilla Hyttnäs and was the one who made all the decisions with regards its interior. He never underestimated the role she played in their marriage and this was evident when you look at his artwork and read his books.

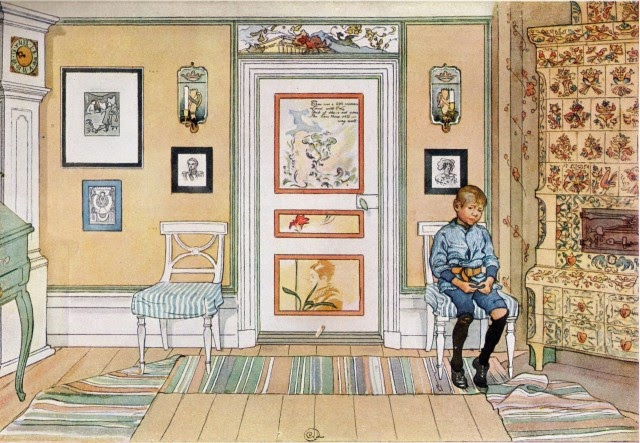

In his book Ett Hem, there is an amusing watercolour by Carl of his son Pontus sitting rather gloomily on his chair in an empty room. Larsson talked about the depiction saying that he took the idea from the sight of a gloomy little boy who had been sent from the table as he had misbehaved during the family meal and had been left to deliberate on his misbehaviour whilst languishing in the beautiful room. Pontus’ bad behaviour was probably not a factor in this work but his punishment was real, that of having to sit still for such a long period whilst his father sketched the scene ! The depiction is probably more about the room itself and the combination of the striped chair covers and rugs, with the tiles of the fireplace.

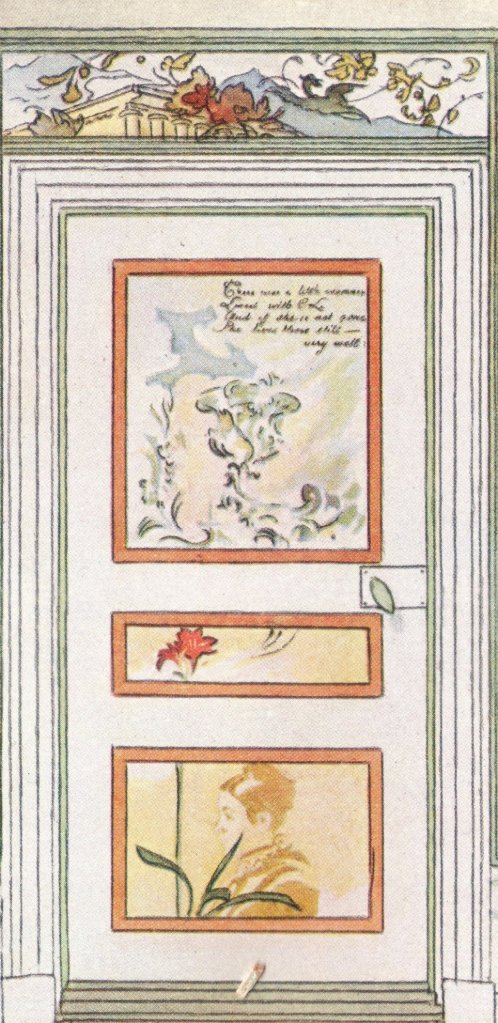

The central part of the painting is taken up by the door. The design of which is a mix of irregularity on the lower panel whilst the panel above is a drawing based on a poem by the English Victorian artist and writer Kate Greenaway’s poem: There was an old woman, who lived on a hill and changed by the artist to There was a little woman who lived with Carl Larsson. Above the door we see decorations, and even though it was a classical temple, it is surrounded by leaves.

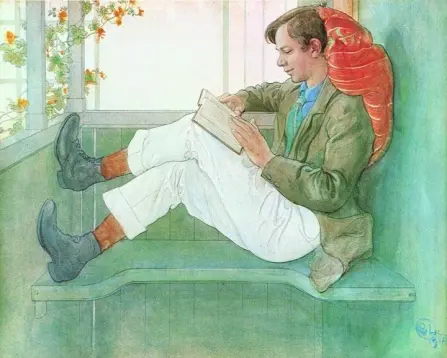

In many of his paintings featuring the interior of Lilla Hyttnäs and his family, reading was a recurring topic and was probably a means of enhancing the idea that his young family were well educated, unlike himself, during his torrid childhood.

Carl and Karin Larsson’s popularity increased considerably with the progress of colour reproduction technology in the 1890s. The Swedish publishing house Bonnier published books written and illustrated by Carl Larsson and containing full colour reproductions of his watercolours, such as Ett Hem. (A Home).

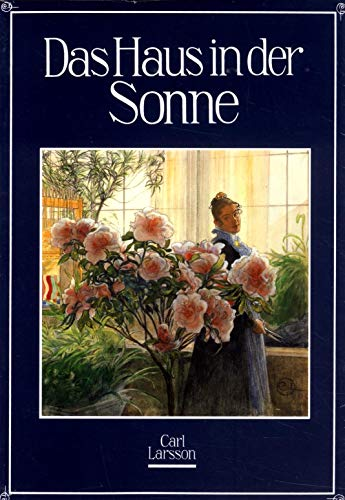

However, the print runs of these rather expensive art books were small in comparison to those published in 1909 by the German publisher Karl Robert Langewiesche. He had chosen a number of Carl’s watercolours, drawings and text by the artist, which culminated in the publication in 1909 0f Das Haus in der Sonne (The House in the Sun), which became one of the German publishing industry’s best-sellers of the year with forty thousand copies sold in three months, and which required more than forty print runs. Carl and Karin were delighted with the success.

Nationalmuseum Stockholm.

For all his paintings depicting his wife, children and beloved home, all his illustrating work for books and newspapers, he considered his large-scale frescoes as his most important work. He created frescoes for schools, museums and other public buildings. In 1907, Larsson completed his mural of Gustav Vasa’s procession into Stockholm, 1523, which was hung with his other commissioned murals in the National Museum in Stockholm, part of a series of murals which he had been working on since the mid-1890s.

In 1915 Carl had just completed his last monumental work, Midvinterblot (Midwinter Sacrifice), which measured 6 x 14 metres (20ft x 46ft). This was yet another fresco commission he had received from the National Museum in Stockholm and this would like several other of his works adorn the walls of the museum. This new fresco painting would be placed on the wall of the hall which led to the central staircase of the museum. The painting, entitled Midvinterblot (Midwinter Sacrifice) depicts a legend from Norse mythology in which the Swedish king Domalde is sacrificed at the Temple of Uppsala in order to avert famine. Larsson was rightly excited with the commission but devastated when the museum rejected the finished work. Larsson was extremely bitter with the museum’s decision. In his autobiography, he wrote:

“…The fate of Midvinterblot broke me! This I admit with a dark anger. And still, it was probably the best thing that could have happened, because my intuition tells me – once again! – that this painting, with all its weaknesses, will one day, when I’m gone, be honoured with a far better placement…”

Later in the book Larsson admitted that the paintings depicting his family and home:

“…became the most immediate and lasting part of my life’s work. For these pictures are of course a very genuine expression of my personality, of my deepest feelings, of all my limitless love for my wife and children…”

The controversial rejection of Larsson’s painting rumbled on well past his death in 1919. Some schools of Swedish artists loved the work whilst others hated it. The painting was never hung in its designated space and the wall remained bare.

In 1987, one artist from the “school of detractors” offered the museum a monumental painting for free, provided it would adorn the empty space but the museum declined the offer. The painting was then sold to a Japanese art collector, Hiroshi Ishizuka, who in 1992, agreed to lend it back to the museum for its major Carl Larsson exhibition. The painting was hung exactly where Larsson had intended. On seeing the giant painting, the public loved it and wanted the museum to buy it from the Japanese owner. With the aid of public and private donations, the museum and the Japanese owner came to an agreed price and in 1997 the painting was purchased by the museum and the painting remained in its “rightful” place and it remains part of the museum collection.

Carl Larsson died on January 22nd 1919 aged 65. His wife Karin died nine years later on February 18th 1928 aged 68.